Peace-Building: If You’re Late, You’re Already Failing

- Frazer Macdonald Hay

- Jul 24, 2025

- 4 min read

Written by Frazer Macdonald Hay

In February 2022, I wrote Prepare for Peacebuilding During the Conflict in Ukraine. It was a simple message: peace-building does not begin when the last gun falls silent. It cannot. If you arrive when the ink dries on a peace accord, you’re not building peace — you’re managing aftermath.

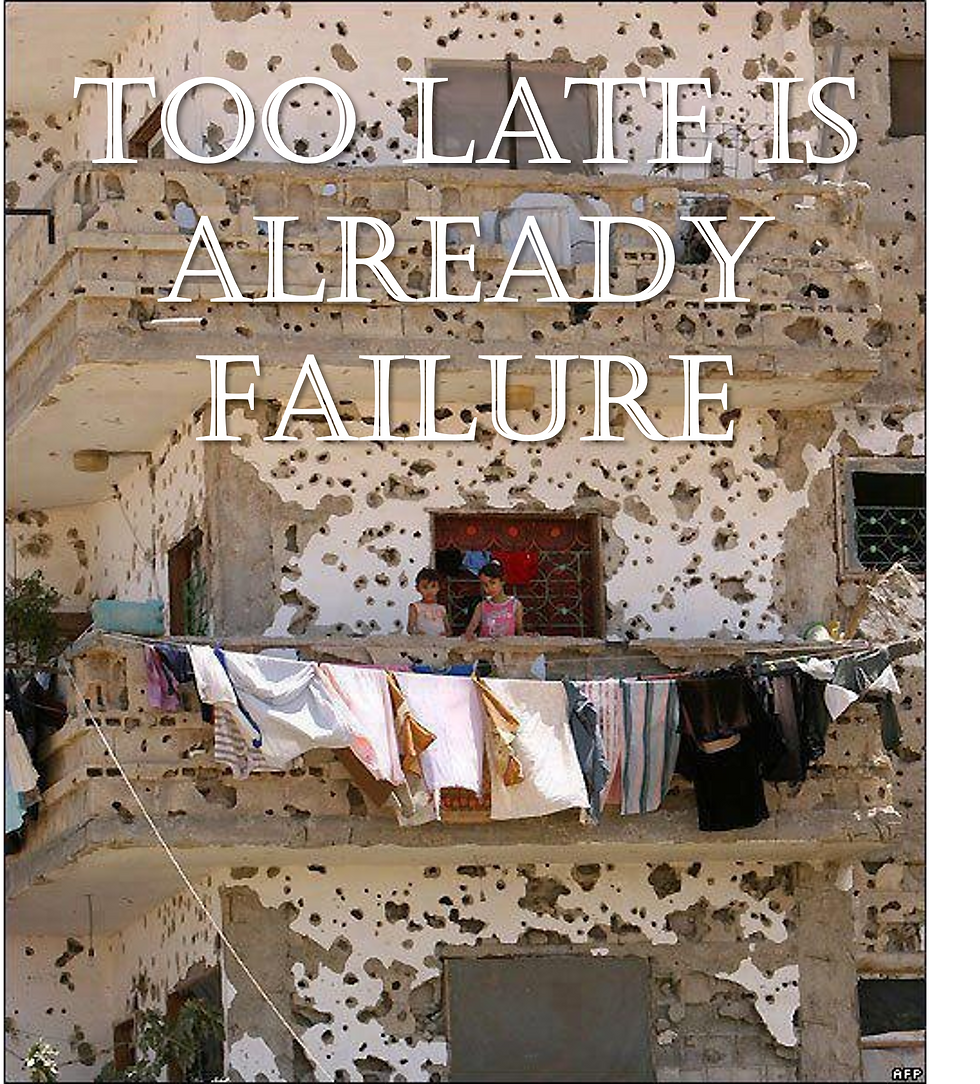

Two years later, the world’s conflicts have multiplied. Gaza burns. Ukraine bleeds on. Sudan, Myanmar, Ethiopia — we watch the updates like sports scores, commenting from conference halls. And still, the same mistake repeats: we wait. We arrive too late, too clean, too detached.

I want to make this point painfully clear: peace-building must begin in war. It has to be shaped in the very conditions of violence. It must breathe the same air as the people it claims to serve — air choked with drone buzz, sirens, distant shelling, bad bread lines, and flickering generators.

Peace Is Not a Post-War Profession

Too many “peace-builders” treat conflict like a post-mortem. They move from one compound to the next — armored convoys, VIP lanes, polite meetings with civil society actors who have already learned the choreography of how to please donors. They rely on locals to interpret a reality they’ve never personally endured. They turn trauma into data points, the frontlines into footnotes.

We send the same cast: ex-military men who once ordered violence now tasked with softening its legacy; bureaucrats skilled at ticking the same boxes in Sarajevo, Kabul, Juba, and Kyiv; newly minted graduates fluent in buzzwords but strangers to the rupture and rawness of conflict.

This is not peace-building. It’s post-conflict project delivery. It’s a career path, a promotion ladder. It is not service.

If You Want to Build Peace, Shoulder Its Weight

True peace-building means entering the conflict zone — not once it is safe, but when it is necessary. It means rushing for the shelter when the siren sounds, queueing for stale bread because there is no supply chain, recognizing the shape of different uniforms in the dusk, knowing which streets might become frontlines overnight.

It means staying long enough to build relationships when they matter most — when trust is a survival tool, not a line in a logframe. It means learning the hazards, the routes, the gossip, the gatekeepers, the grief.

Empathy is not an exercise in distant compassion. It is forged in shared experience — not abstract “solidarity” but the simple fact of living through risk together. If we fail to shoulder even a fraction of the burdens our partners bear daily, how dare we speak of peace?

We Cannot Outsource Conflict

Our approach is upside down. We rely on local actors for our fieldwork — they do the dangerous parts. We extract knowledge from them, but rarely share the risk. We hire them to gather evidence for our reports and evaluations. We brand it “participation.” We call it “localisation.” We give them frameworks while we keep ourselves walled off.

Meanwhile, the conflict mutates and metastasizes beneath our tidy theories. Spoilers and opportunists slip between the cracks of our ignorance. Corruption, capture, and fatigue fill the voids we leave behind.

By the time we “intervene” with workshops and policy papers, communities have endured a thousand cuts of violence and betrayal. And we wonder why they greet us with cynicism, see us as just another cost to bear.

Gaza. Ukraine. The Thai Border.

If you want to build peace in Gaza, you need to be there now — not in the rubble after. You need to understand how a siege breaks a street, a neighbourhood, a family. You need to see how aid convoys are blocked, how people smuggle flour, how children grow up counting drones like stars.

If you want to build peace in Ukraine, you need to be there now — navigating the politics of occupied towns, the fatigue of cities under endless sirens, the hidden networks that keep daily life stitched together. If you want to prepare for peace on the Thai-Myanmar border, you need to be listening now, before the next wave of displaced people becomes just another statistic.

Send the Generals Home

This is not a polite plea for better programming. It’s a demand for a different culture altogether. Send the ex-military officers home — let them account for their legacies elsewhere. Assimilate the bureaucrats into local structures. Call out the “peace-building elite” who drift from conflict to conflict polishing CVs while never stepping outside the compound walls.

If you cannot share the discomfort — the shelters, the bread lines, the sleepless nights — then at least stop pretending you know what peace requires.

Peace Is Not a Product — It’s a Practice

Peace is not something you “deliver.” It is something you live with people who have no choice but to live through war. If you want credibility, earn it by standing where the shells fall. If you want trust, share the risks. If you want impact, stop showing up late with your well-funded frameworks and your exit plans already drafted.

If you want to build peace — do it now. During. Not after.

Read the original 2022 piece here: Prepare for Peacebuilding During the Conflict in Ukraine

#PeacebuildingNow #ConflictZonePeace #PeaceDuringWar #PrepareForPeace #BuildPeaceNotJustPostConflict #RethinkPeacebuilding #TooLateIsFailure #BeyondTheCompound #ShoulderTheRisk #SharedBurden #GazaPeace #UkraineWar #MyanmarConflict #ThaiMyanmarBorder #WarAndPeace #HumanitarianAction #SolidarityInConflict #LocallyLedPeace #ConflictResolution #PeaceIsPractice #SendTheGeneralsHome #PeaceIsNotAProfession #EmpathyInConflict #ListenInTheWar #InvestInPeace